Mastroeni, Arena & American soccer’s cult of coaching insecurity

As most readers will know, the United States has never won a World Cup in men’s international soccer, at any age level.

Nor has the program ever occupied first place in the FIFA World Rankings, having topped out at its all-time best position of No. 4 back in 2006 – and FIFA has changed the calculation formula significantly since then. The USMNT’s current placement at No. 23 in the world is a lot closer to the norm, given the Yanks’ average ranking of 20th since the FIFA rankings’ inception.

In general the country is still seen as a frontier of the beautiful game, with plenty of catching up still to do despite a quarter-century of marked and dramatic advancement in the sport.

And yet, despite of all the obvious realities of the USA’s junior position in the world pecking order, some American coaches at all levels make a habit of waving off – or even openly mocking – innovation, outside knowledge, industry-leading best practices and even slightly unfamiliar perspectives.

And yet, despite of all the obvious realities of the USA’s junior position in the world pecking order, some American coaches at all levels make a habit of waving off – or even openly mocking – innovation, outside knowledge, industry-leading best practices and even slightly unfamiliar perspectives.

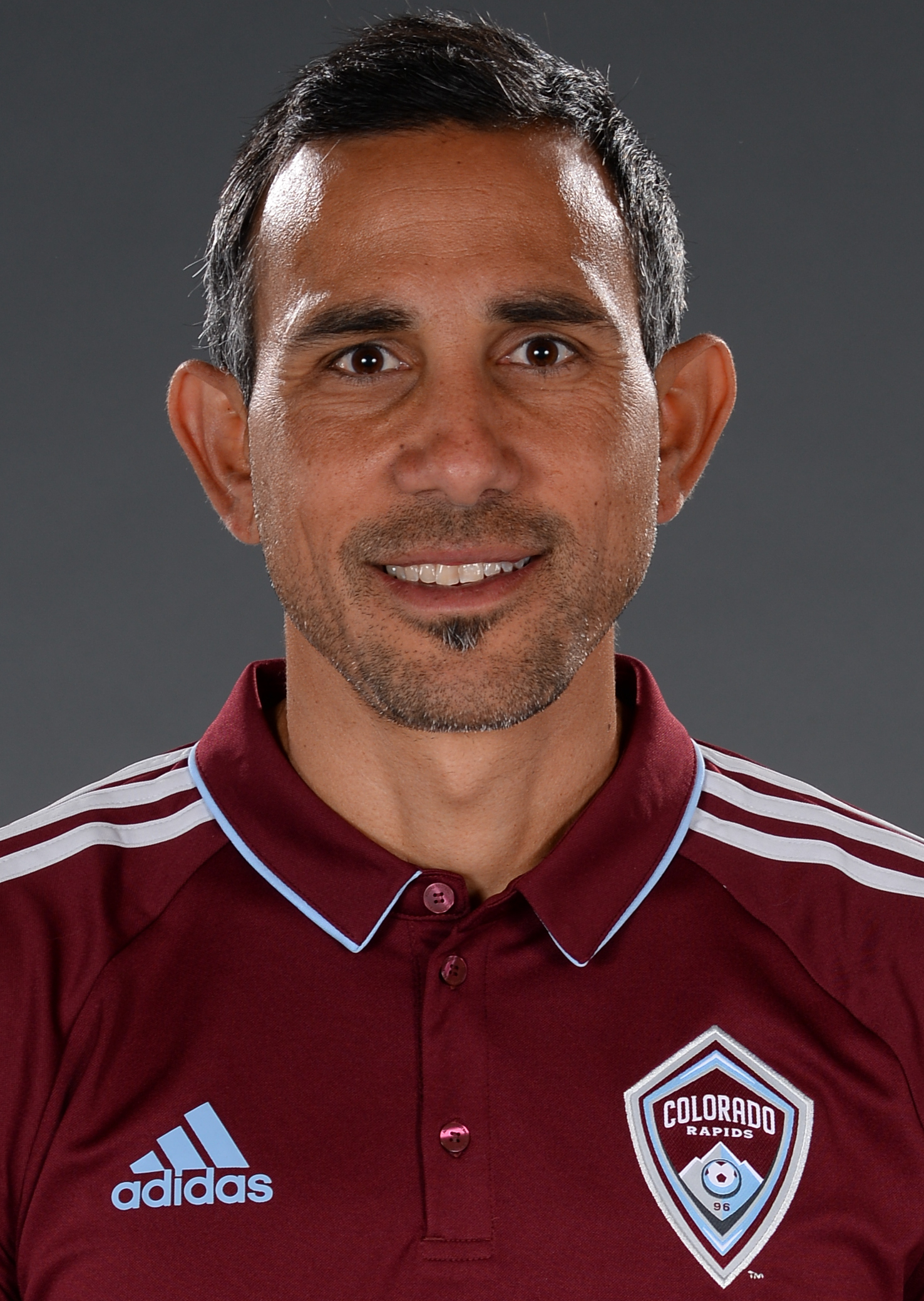

Colorado Rapids head coach Pablo Mastroeni tossed out the latest bucket of chum after his team’s 1-0 win over Sporting Kansas City last weekend. In postgame remarks which have quickly gone viral among parts of the American soccer community, the former US international and World Cup veteran assailed the fairly logical idea that his team’s victory came in contrast to the game’s overwhelming character.

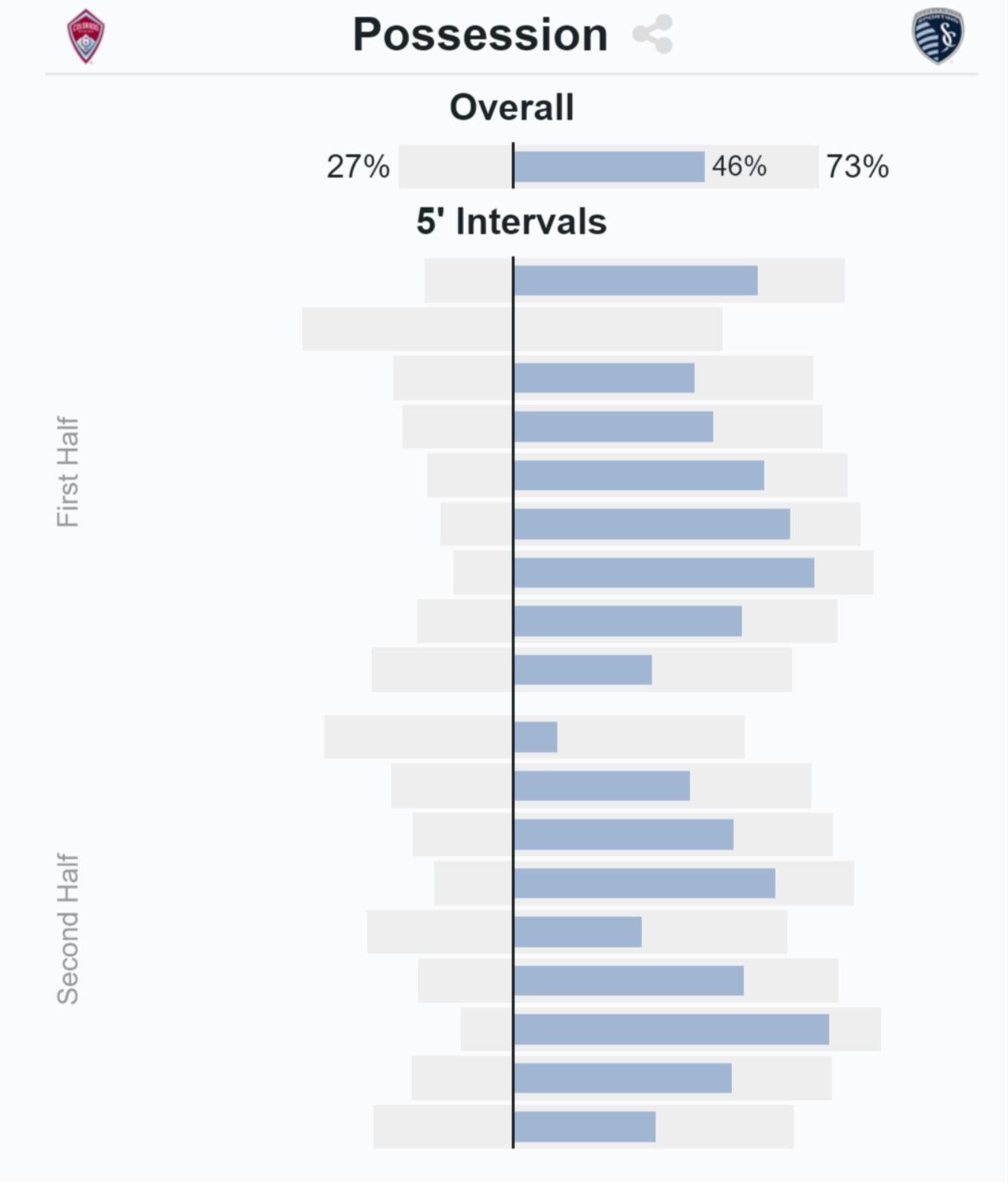

Taking an early lead via Kortne Ford’s 11th minute set-piece header and then hanging on to it for dear life, the last-place Rapids were out-shot 24-6, lost the possession battle by a whopping 73- to-27 percentage margin and completed just 225 passes compared to 629 for the Western Conference-leading visitors from KC. And quite frankly, they were hard to watch from a neutral or aesthetic perspective.

“The pundits and the people who like to comment on the game will look at possession and will look at shots and will look at all kinds of other metrics that have very little to do with heart and courage and commitment for one another,” opined Mastroeni. “And I think that’s what we haven’t had this year. We’ve had some pretty football games, and you know what, we’ve lost those.”

The win was only the third of the season for Colorado, who fell just short of winning the 2016 Supporters’ Shield but have looked a shadow of themselves this year as they attempt to cultivate a more assertive attacking posture compared to their previous stolid defensive approach.

You could hardly tell by the triumphant tone of their leader – who is on the first head coaching job of his career, having moved straight into the job after hanging up his cleats in 2013 – on Saturday, however.

“It’s OK to be who we are. It’s OK that we don’t have 150 passes in 30 minutes, it’s OK if we don’t have 150 shots on goal. This game is about winning, it’s about thinking the game,” continued Mastroeni. “People have lost the plot with all this passing and shooting percentages and if you shoot from here you’ll score if you do it 12 times … Stats will lose to the human spirit every day of the week.”

The Argentinean-born coach is continuing a proud tradition of Know Nothing-ness which has enjoyed a roaring comeback following the unceremonious end of the cosmopolitan Jurgen Klinsmann’s time in charge of the USMNT. The standard-bearer, in fact, is Mastroeni’s former boss and Klinsmann’s replacement Bruce Arena, who regularly fires off similarly anti-intellectual, anti-analytics rants.

“We won the game. That’s what you do in soccer games,” Arena famously said after his LA Galaxy were dominated by the Portland Timbers in nearly every facet save the final score last year.

“We won the game. That’s what you do in soccer games,” Arena famously said after his LA Galaxy were dominated by the Portland Timbers in nearly every facet save the final score last year.

“Then some moron will write that they had more shots than us thinking that’s important. Actually, analytics in soccer, if no one here has figured it out, doesn’t mean a whole lot. Analytics and statistics are used for people who don’t know how to analyze the game.”

It’s tempting to ascribe this mindset to a simple mis- or poor understanding of the advanced number-crunching which has become influential at many of the world’s top club and national teams. But Arena and Mastroeni have shown a wider and more general distaste for outside perspectives.

“Coaching is coaching. No one in Europe knows anything more about soccer than we do,” he told reporters less than a year ago, suggesting that he can learn more from an NFL coach like Bill Belichick than the likes of Manchester City boss Pep Guardiola. “The drills we use are the same ones they use.”

Europe has produced 26 of the 40 teams which have contested the 20 World Cup finals since the event began back in 1930. The other 14 hail from South America, the other unquestioned fountain of continental soccer excellence. And even the greatest minds from those two regions tend to emphasize the extent to which they’ve stood on the shoulders of giants.

“I’m no innovator,” Guardiola, winner of three German, three Spanish, two UEFA Champions League and three Club World Cup titles as a coach, once famously insisted. “I’m an ideas thief.

“Ideas belong to everyone and I steal as many as I can.”

“Ideas belong to everyone and I steal as many as I can.”

He and others of his caliber regularly extol the myriad complexities of the game they love, continually exploring for new perspectives and unfamiliar concepts to fuel – hell, even just to keep pace with – the constant, ruthless evolution found at the sport’s uppermost reaches.

With his litany of achievements at the college, pro and international level, it’s no bold statement to call Arena the most successful coach in American soccer history. But he and acolytes like Mastroeni reveal the true extent of gap between this country and the global elite when they flash their insecurities so proudly and publicly.

What we portentously refer to as “analytics” or “big data” is really just information. And what coach or leader doesn’t seek out and use information to make their decisions?

Mastroeni’s team were second-best on Saturday in most measurable and visible components of soccer quality. Regardless of the final score on the day, more of the same over the much broader sample size of a full season is highly unlikely to bring them success of any great magnitude.

Mastroeni’s team were second-best on Saturday in most measurable and visible components of soccer quality. Regardless of the final score on the day, more of the same over the much broader sample size of a full season is highly unlikely to bring them success of any great magnitude.

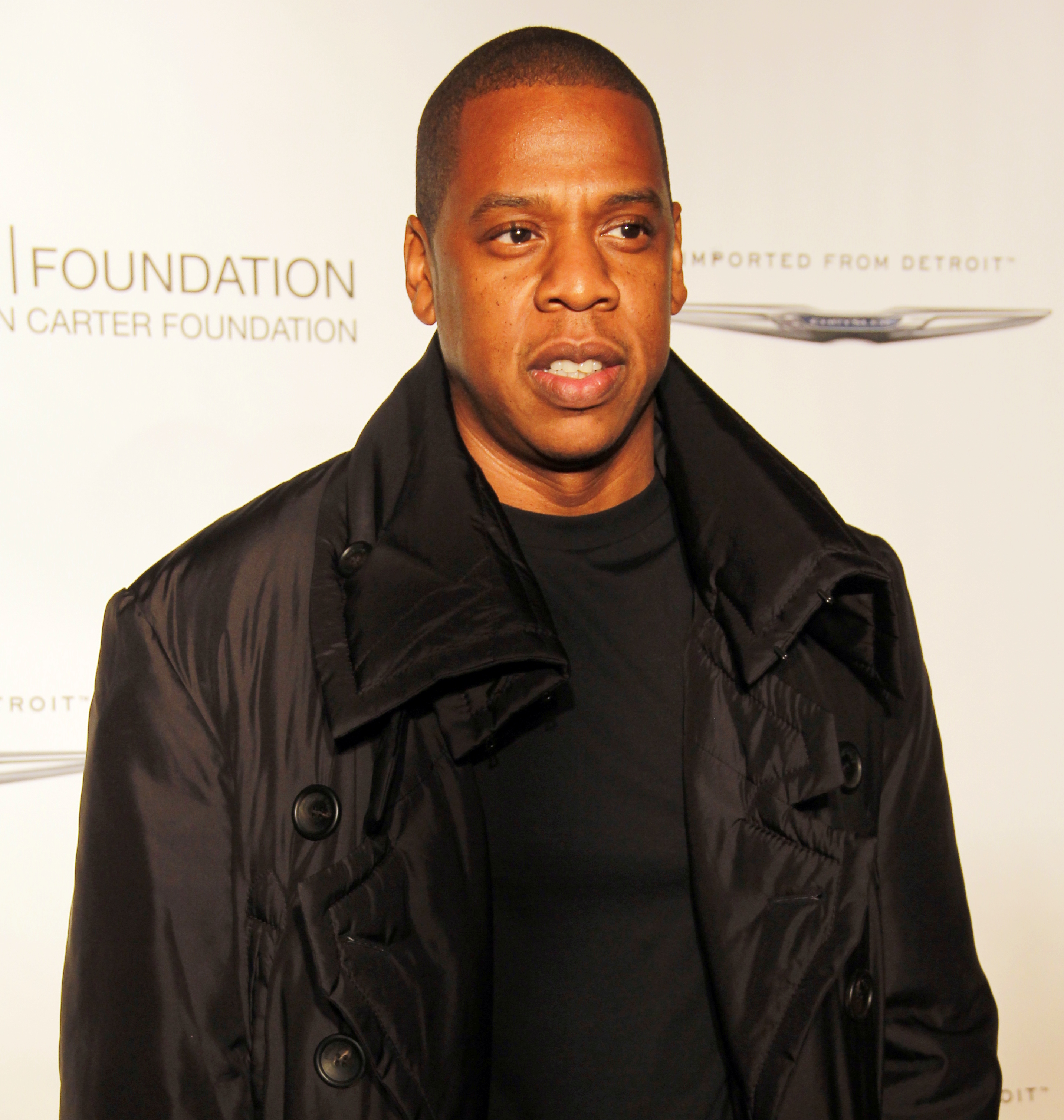

One of my favorite-ever interview moments came in 2010, when Terri Gross of NPR’s “Fresh Air” asked Jay-Z why so many rappers grab their crotches so often.

“In hip-hop … usually you have a hit record and then [record executives] throw this person on stage who has never been on stage before. So they don’t have any experience on how to perform in front of people, hold the mic – all these different things you need to know,” he responded.

“So you get up there, you feel naked. So when you feel naked, what’s the first thing you do? You cover yourself. So that bravado is an act of, ‘I am so nervous right now. I am scared to death. I’m going to act so tough that I am going to hide it, and I have to grab my crotch.’”

Mastroeni’s show of bravado betrays a similar scenario. “Heart and courage and commitment” are very important elements of his business. They’re also baseline expectations for professionals and don’t comprise a fully-baked tactical or philosophical plan.

Mastroeni’s show of bravado betrays a similar scenario. “Heart and courage and commitment” are very important elements of his business. They’re also baseline expectations for professionals and don’t comprise a fully-baked tactical or philosophical plan.

Yet they’re his area of expertise, so it’s natural that he emphasizes their impact and lashes out against a perceived quest by “stats nerds” to usurp the pole position that he believes his playing career has earned him.

Many Americans harbor deep-rooted anxieties about our relatively humble place in world soccer compared to our wider status as a superpower. That’s entirely understandable.

But if we continue to do what we’ve always done, we will continue to get what we’ve always gotten: Also-ran status, via players, coaches and teams of only modest quality when viewed on a global scale.

SOCCERWIRE MARKETPLACE

- visitRaleigh.com Showcase Series 2025, hosted by NCFC Youth

- OFFICIAL MANCHESTER CITY SOCCER CAMPS

- Wanted Licensed Youth Soccer Coach

- Join Official Elite Summer Soccer Camps with Europe’s Top Pro Clubs!

- The St. James FC Travel Staff Coach - North (Loudoun) & South (Fairfax)

- The St. James FC Girls Academy (GA) Head Coach - 2 teams

- The St James FC Boys Travel Tryouts

- OFFICIAL BAYERN MUNICH SUMMER CAMPS U.S.

- JOIN THE ALLIANCE!

- OFFICIAL FC BARCELONA CAMPS U.S.