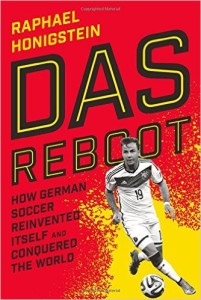

“Das Reboot” reviewed: Raphael Honigstein’s lively, insightful work a must-read for coaches, players, administrators

In Das Reboot, the brisk and lively new book about the German soccer revolution, author Raphael Honigstein chronicles the reforms that both transformed German soccer and manifested themselves within Germany’s 2014 World Cup triumph.

Early in the book, Honigstein introduces us to Dietrich Weise, a former Bundesliga club and youth national team coach (you can read an excerpt from this section here).

Early in the book, Honigstein introduces us to Dietrich Weise, a former Bundesliga club and youth national team coach (you can read an excerpt from this section here).

In spring 1998, Weise presented a comprehensive coaching reform plan to then-president of the Deutscher Fußball-Bund (DFB) Egidius Braun.

“There were big differences as far as the federal associations’ ability to look after the kids was concerned,” Weise tells Honigstein. “Some didn’t have the finances, some didn’t have the manpower. We thought that was unfair. Every kid playing in Germany should have the same opportunities.”

Somehow, despite a massive soccer infrastructure and thriving professional clubs, the German system was comprehensively failing some of its most talented young players.

Weise’s plan then was a total overhaul of the methods used to train and identify young German players: use 115 regional training centers to spot and develop talented young players and then help the regional federations do more to develop the best players in their catchment areas.

It was a persuasive pitch, but Braun balked at the price tag: 1.25 million Euros.

+NEW PODCAST: The SoccerWire Show breaks down U.S. U-17s with special guest Travis Clark

“It wasn’t enough to have a few coaches at the regional federations,” Weise recalls to Honigstein. “And the fathers who were coaching youngsters in their spare time in many clubs didn’t have any real qualifications either. That’s not sufficient. Papa can’t be the solution!”

After Germany’s disastrous quarterfinal exit in that summer’s World Cup, the DFB board approved Weise’s plan, providing the funds to set up 121 regional centers. Each would provide several hours of coaching, once a week, for thousands of teenaged German players.

Such were the humble beginnings of what has become a soccer revolution.

Such were the humble beginnings of what has become a soccer revolution.

Meanwhile in the United States, the U.S. Soccer Federation wasn’t without its own comprehensive reform plan. After the U.S. National Team’s own woeful performance at the 1998 World Cup, USSF revealed Project 2010, an in-depth look at the troubles besetting U.S. soccer from the grassroots level up and a series of recommendations meant to rectify them.

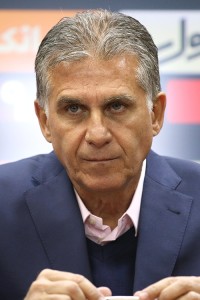

The study’s author, coach Carlos Queiroz, wrote with bracing honesty that: “No one should be surprised about the performance of the U.S. Team in France. It was a natural occurrence — nothing more nor less than the reality of soccer in the United States.”

+READ: Froh: U.S. U-17s still alive, but just barely after 2-2 World Cup draw with Croatia

He went on to diagnose one of the great problems in U.S. soccer, the lack of quality coaching and the lack of infrastructure to help identify the most talented players in every region of this massive country.

“We need to think big,” he wrote. “This means setting up a competitive infrastructure, with heavy involvement from state associations, enabling the game to grow stronger naturally at the local level. This is extremely important, because if the game isn’t strong at the local level and isn’t pushing everything up from the grassroots, then any success we experience at the national team level would have to be considered artificial.”

But where Germany acted after what it deemed an unacceptable international result, the U.S. wavered. To this day, few of Quieroz’s proposed reforms have been implemented. Media and fans in the U.S. still search for what Quieroz termed “the magician,” a coach who “somehow, despite all the limitations of our player identification system, can find a way to take the U.S. team to newfound success.”

While Jurgen Klinsmann was heralded in the United States as a kind of soccer savior, in his native Germany, Klinsmann was far from a “magician.” Yet Klinsmann was, as Honigstein illustrates, a critical component of Germany’s transformation, providing the ideological shake-up necessary within the upper echelons of German soccer.

The value in Klinsmann’s ideas, however, was not immediately evident to the decision-makers in German soccer.

Only months before the 2006 World Cup and after a series of poor results that culminated in Germany’s 4-1 loss to Italy in a friendly, the media predictably began calling for Klinsmann’s ouster. Honigstein quotes some of the dissenting opinions, opinions that by now may appear familiar to American readers.

Wrote Focus magazine: “Klinsmann, who has already shown a streak of egomania as a player…is a dreamer, a loner who is more of a guru than a strategist. He bullies experienced pros out of the squad and unsettles the young ones…He could have sought the help of experienced Bundesliga coaches but wanted to do everything by himself. A novice and a know-it all – a dangerous combination.”

Wrote Focus magazine: “Klinsmann, who has already shown a streak of egomania as a player…is a dreamer, a loner who is more of a guru than a strategist. He bullies experienced pros out of the squad and unsettles the young ones…He could have sought the help of experienced Bundesliga coaches but wanted to do everything by himself. A novice and a know-it all – a dangerous combination.”

But while it would be easy to dismiss Klinsmann’s contributions to Germany’s World Cup success – the profound systematic changes within the DFB and the Bundesliga academy structure (such was the change, in fact, that by 2011 more than half of all Bundesliga players had been in BL club academies) had begun years earlier – Klinsmann’s outside-the-box thinking and approach to Germany’s soccer problems has since permeated almost every level of German soccer.

Before Klinsmann, say several of Honigstein’s interview subjects, the DFB was a stale soccer environment suspicious of outsiders and foreign influences.

+READ: Maybe Klinsmann’s $2.5 million salary would be better spent elsewhere

“The first, big, heavy stone that was thrown at the glass window came from Klinsmann,” ZDF sports editor Jan Doehling tells Honigstein. “He kicked open the doors and decreed that there shouldn’t be any more doors in that place from now on, to let some air in. He was the locomotive, the trailblazer. Everyone else just followed in his slipstream.”

Those shifts in attitude have yet to manifest themselves within American soccer and may never. To read Das Reboot as some kind of guidebook for soccer reform in this country is foolish. The vast chasm between the American and German soccer cultures (and the book teems with examples that amply demonstrate those differences) likely explains why reform gained more traction in Germany than it ever has here.

Das Reboot, though, is not a book about Jurgen Klinsmann, but rather one abounding with insights about coaching and player development (“The biggest, most decisive effect resulted from the increase of full-time professional youth coaches,” says Ulf Schott, director of the DFB). Above all, it is a fascinating story well-told and a must-read for coaches, players, fans and administrators at every level of the U.S. soccer pyramid.